Superfood Man

February 11, 2012 –

This was an article in business week with the infamous Darin Olien, co-creator of Shakeology. As we lead up to Vegan Shakeology tropical, the timing could not be more perfect.

For the source article, click HERE

January 26, 2012, 7:00 PM EST

The Adventures of Superfood Man

Darin Olien is to maca root and goji berry what Indiana Jones is to lost arks. And the market for his exotic drink mixes is doubling—even though there’s scant science to show they work

By Peter Heller

On a good morning in Paradise Cove, Malibu, the water is so clear you can see halibut lurking in the kelp. Little Dume Point rises from its cliffs to the north, and beneath it a few surfers on stand-up paddleboards rise and fall on the swell waiting for their wave.

On a good morning in Paradise Cove, Malibu, the water is so clear you can see halibut lurking in the kelp. Little Dume Point rises from its cliffs to the north, and beneath it a few surfers on stand-up paddleboards rise and fall on the swell waiting for their wave.

Darin Olien, who looks like a Tarzan action figure, is talking to a surfer in his early twenties named Igor about the health benefits of alkalinization in the body. He tells Igor, who’s trying to balance his board and blinking back the sun, that 7.4 is where the pH of our body wants to be and that most of our diets are far too acidic, which leads to inflammation and degenerative disease. Red meat is very acidic; coffee, corn, and wheat, too.

“Hold on,” Olien says. He pivots his stand-up board and hooks on to a wave, muscles rippling, blonde curls flying. The board, essentially a longer, beefed-up surfboard designed to be paddled while standing up, was designed by Olien’s buddy, Laird Hamilton, the legendary big wave surfer. When Olien paddles back out, his grin is wide, white, and infectious. “This connection with the ocean … water is so vital.” He starts telling Igor about the biochemistry of proper cellular hydration. The kid is polite, nodding along. It’s hard to resist the enthusiasm of Superfood Man.

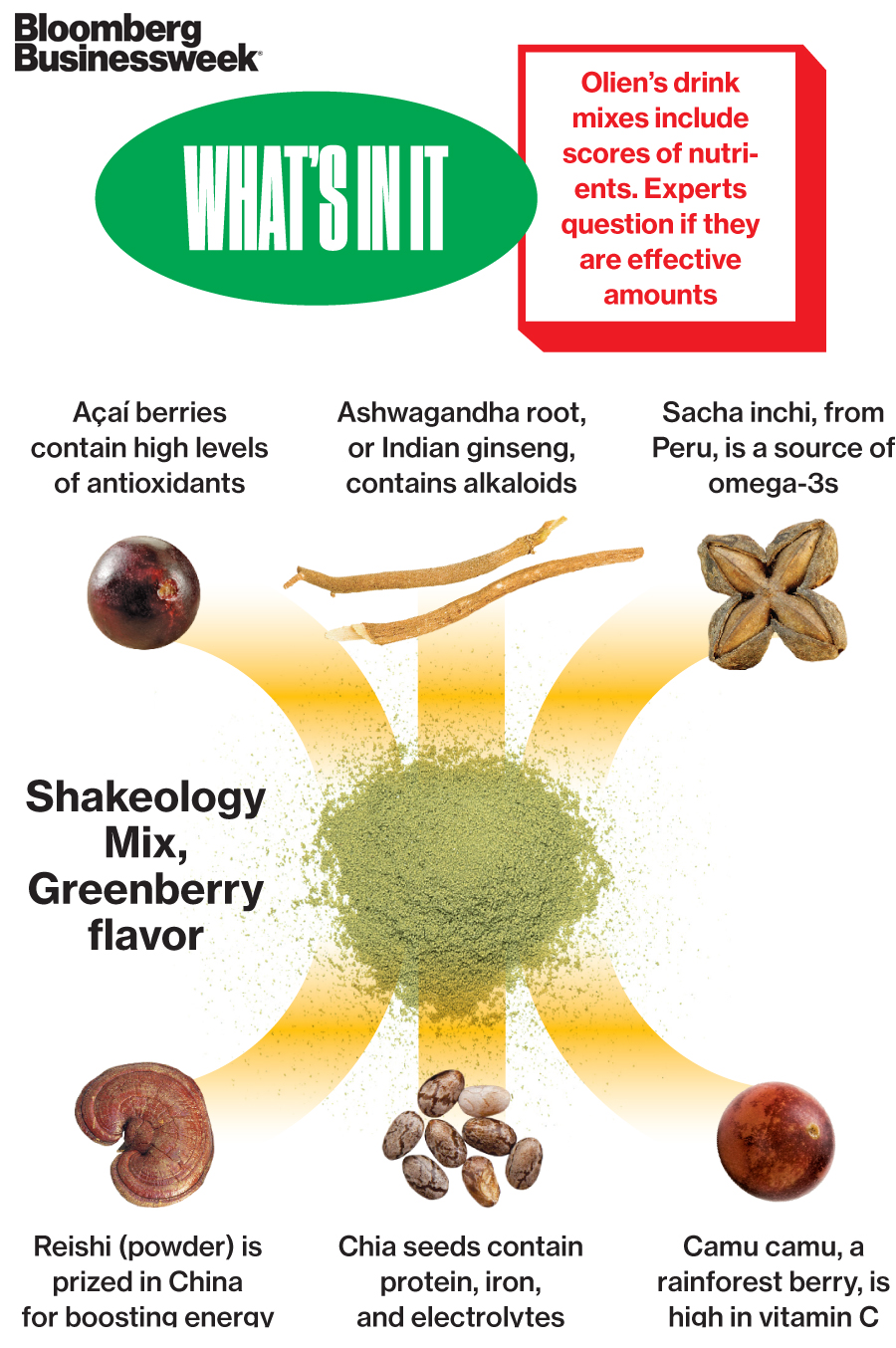

Olien, who has traveled in the past two years to Peru, Indonesia, Costa Rica, Bhutan, and China in search of underappreciated fruits, nuts, and grains, may be the most aggressive hunter of superfoods on the planet. A superfood, according to Olien’s Facebook page, is “a natural food regarded as especially beneficial because of its nutrient profile or its health-protecting qualities.” The category includes such well-known domestic fruits as blueberry and pomegranate, as well as little-known exotics such as maca root and goji berry, sacha inchi, and ashwagandha root. Many of the exotics have been consumed for their health-giving properties for thousands of years by indigenous peoples. Olien has cultivated the persona of Raider of Lost Nutritional Knowledge. “We aren’t discovering anything,” Olien says. “My greatest gift is showing up. Listening. Asking questions.”

His timing could hardly be better. Millions of health-conscious Americans now heed the advice of such TV personalities as Dr. Mehmet Oz, who says people are better off getting dietary fiber and nutrients from whole foods (rather than mass-produced vitamins). Drinks such as POM Wonderful, which in 2011 said it expected to sell 3 million cases, have expanded the market for foods and drinks rich in antioxidants, molecules that promote health by protecting cells. Popular weight-loss and athletic-performance diets, such as the Paleo Plan, based on what humans ate before agriculture, stress the wisdom of the ancients.

In 2006, Olien joined up with the infomercial and multilevel marketing powerhouse Beachbody (the company behind the P90X home exercise program) and formulated a superfood-rich meal-replacement powder they call Shakeology. Olien is under contract with Beachbody, gets a royalty from Shakeology sales, and the company picks up some travel expenses. What they sell is a chocolate- or berry-flavored powder you mix with water or milk or juice, usually in lieu of a normal breakfast. Six years later, the company sells 2 million 1.7-ounce servings a month to 66,000 subscribers who pay $120 for a 30-day supply. The shake brings in over $100 million annually. Beachbody Chief Operating Officer Seth Tuckerman declined to reveal profit margins. Tuckerman, who came over from Gerber Products, and Carl Daikeler, Beachbody’s chief executive officer and majority partner, say that while sales of dietary supplements in multilevel marketing channels declined 1 percent in 2010, Beachbody’s Shakeology is growing 100 percent per year. By word of mouth. No infomercials and no advertising—beyond, that is, the indefatigable efforts of Olien.

If there were a comic book Superfood Man, he’d live in Malibu, in a sage-green bungalow just like Olien’s, tucked away in a dense grove of eucalyptus trees half a mile from Zuma Beach. A 38-year-old horse named Moonlight comes to the fence to keep Olien company when he sets his chair out in the sun to eat the big salads that are his staple diet. Olien, 40, hails from Waseca, Minn., and has been a vegetarian for 10 years. He has a master’s degree in psychology from the University of Santa Monica. His interest in nutrition dates to a back injury he sustained playing football at Augsburg College in Minneapolis, when he tried to use diet to reduce swelling and recover the full motion of his limbs.

Inside, the decor is austere, with a few artifacts from Olien’s travels—a didgeridoo from Australia, a flag from Bhutan. A futuristic machine that distills pure water from the air rests in the kitchen. His desk chair is a snow-white exercise ball. Such details might seem trivial, but Olien has a keen eye for them. In Shakeology’s marketing materials, he’s seen paddling a dugout through jungles, hiking Andean mountainsides, and riding beat-up Third World motorcycles to arrive at remote farms where he kneels and sifts dirt that has never seen a pesticide. The booklet that accompanies your first order of Shakeology carefully builds on the same theme: The cover looks like a leather-bound explorer’s journal, and the story of each ingredient is an adventure told on torn diary and stamped passport pages that includes “swimming with crocodiles to acquire papain,” an enzyme in papaya.

Shakeology now accounts for 20 percent of a business that also sends out 2 million fitness DVDs a month, and yet much of the shake’s blending is done by Olien alone, in the bungalow’s small back bedroom. On floor-to-ceiling shelves sit jars and jars of precious powders—beige, ochre, and green—labeled with strips of masking tape, the dried and milled grist of roots and fruits and seeds, each with its own alleged powers. There are also two precise formulator scales and notebooks with the results of the battery of lab tests that are performed on each powder, from the initial bacterial counts for food safety to micronutrient and phytochemical profiles. Olien uses his own body as a guinea pig before bringing his blends to a food lab for final formulation. “My body is the first barometer,” says Olien.

Meal-replacement shakes are a vibrant, if nebulous industry, with its roots in early attempts to control obesity. In the 1960s a University of California at Los Angeles study found that starvation as a treatment for extreme obesity was effective, but that for every four pounds of body weight lost, the subjects also lost a pound of muscle. In the ’70s, protein shakes such as Optifast (now owned by Nestlé (NESN:VX) ) and Unilever’s Slim-Fast were developed to address the problem, and Abbott Laboratories (ABT) came out with Ensure, a balanced diet drink that could be fed to hospital patients unable to eat whole foods. All three have been adopted enthusiastically by the weight-loss industry and are market leaders. According to the Nutrition Business Journal (NBJ), the meal-replacement industry grew 4 percent in 2010, to $2.8 billion. Ensure accounts for the lion’s share. According to Chicago market research firm SymphonyIRI Group, Ensure brand sales, excluding those at Wal-Mart (WMT), grew 4.7 percent, to $252.7 million. NBJ estimates total sales at more like $500 million.

The packaging for Shakeology features the slogan, “The Healthiest Meal of the Day,” but it may not be a true meal-replacement shake. While the Food and Drug Administration has no legal definition for meal-replacement powders, or MRPs, Olien says Beachbody may move away from the term so as not to get crosswise with industry standards. The basic Ensure shake has 250 calories and 9 grams of protein. Shakeology has 150 calories and 18 grams of protein—so it’s light on calories for a meal. It does qualify as a dietary supplement as well as a superfood supplement, and it vies with protein shakes such as Muscle Milk. (Muscle Milk sales, excluding those in Wal-Mart, grew 32.3 percent, to $51.6 million, from 2010 to 2011, says SymphonyIRI.)

Shakeology’s success may be explained by its ability to occupy a niche at the intersection of these categories; the categories themselves are slippery. Carla Ooyen, director of market research at NBJ, laughs and concedes: “There are fine lines between meal replacements and harder core sports nutrition products. A lot of it is marketing. In 2010 sports nutrition grew 9 percent, to $3.2 billion.” She says sales of such superfruits as açaí, mangosteen, and noni increased between 200 percent and 400 percent in 2005 and 2006 but have since flattened. What’s most striking about Shakeology’s rise, however, is not that it has outperformed these trends, but that it has done so without clinical trials to prove that its superfoods are, in fact, super.

Beachbody’s chief science officer is Bill Wheeler. He’s a hearty, white-haired PhD in a glass-fronted office. He wears a silver belt buckle from his days as a roping cowboy in Colorado. His résumé includes a stint as the staff nutritionist to the President of the United States. Both Carter and Reagan. In 2001 he started a nutrition consulting business that advised the Green Bay Packers, Utah Jazz, and Denver Nuggets, among other pro teams. Brett Favre depended on him to tell him which of the piles of free supplements the team received wouldn’t trigger false positives on drug tests. “There are stacks of studies on most of these ingredients,” Wheeler says, referring to Shakeology’s ingredients. “You can look them up. We are conducting a full-scale clinical trial on Shakeology, 100 people, 100 days, double-blind. At a university medical school.” (Wheeler wouldn’t disclose when the results would be published.)

How do Wheeler and Olien know how much of each superfood to put in? “We go to the user country,” says Wheeler. “What is the observed use of it? We form a collaboration with experts in that area, take that as a start. Make a WAG, a wild ass guess. What does it contain? What are the effects?” Take maca root, he says. “If it’s used as a sexual stimulant you’d probably use 10 grams; 500 milligrams to a gram as an adaptogen [a remedy that prevents unwanted stresses]. We look at all the science, the historical data, the literature, and make a SWAG. A scientific wild ass guess.” He leans across his desk. “Sometimes you can’t wait for all the science. In 1853, a British naval surgeon said one lime a day would prevent scurvy. It was 1920 before we knew the active compound was vitamin C. If they had waited for the science, how many would have died in 70 years? There might not be a British Navy. There might not be an England, which might not be a bad thing.”

Dr. Susanne Talcott, assistant professor of toxicology and a director of research at Texas A&M’s Nutrition and Food Science Dept., specializes in testing superfoods. She conducts animal trials, human clinical trials, and cell culture tests on a whole range of foods. For this article, she agreed to review the ingredients and amounts on the fact sheet of a serving of Shakeology. Aside from almost three eggs’ worth of protein, vitamins, and minerals, there seemed to be a tad of almost every superfood known to the herbal-loving world, she says. Shakeology’s Adaptogen Herb Blend, for instance, has a combined 1,675 milligrams of maca (root) powder, astragalus (root) powder, cordyceps, schisandra (berry) powder, and suma (root) powder, among others. The Antioxidant Blend weighs in at 1,750 milligrams per serving and includes standards such as blueberry as well as goji and açaí. A third “phytonutrient super-green” blend adds 1,800 milligrams. Talcott did some fast math in her head. “If we add up the amounts of each of these blends, we are looking at about 5 grams. You say these are not extracts. So, we expect 1 percent to 2 percent secondary bioactive compounds. That would be some 50 milligrams.” She explained that the amounts she uses in clinical trials are usually much higher, varying from one to two grams a day, to 7.5 grams per kilo of a subject’s body weight. She says, at first glance, “I think it might be a terrific product.” But she cautions, “I cannot answer whether the amounts provided here contain enough bioactives to indeed have [a positive] effect.”

Neither can the FDA. Dr. Daniel Fabricant, director of the Division of Dietary Supplement Programs at the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, says that under a 1994 law called the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, companies don’t even have to notify the agency of their ingredients, as long as they were marketed in the U.S. before 1994 and they haven’t been chemically altered. “We’re going to take them at their word,” he says of Beachbody. As far as health claims, he says: “Statute requires they have substantiation of their claims.”

Mark Blumenthal, executive director of the American Botanical Council, a trade group for herbal remedies, is more critical. “The whole plant dried is not as concentrated as some extracts,” he says. To use more concentrated extracts could cost four times as much, he says, and as it is, Beachbody charges a premium. How does the company justify it? Blumenthal answers his own question: “Construct a compelling story.”

Which is exactly what Beachbody has done. It feeds on testimonials. “Once people go through a dramatic transformation—they lose weight, their cholesterol goes down, they have more energy—they just can’t stop talking about it, ” says COO Tuckerman. Moreover, “when anybody hangs out with Darin, they just want to be like him.”

Two days after surfing in Paradise Cove, Olien is up at Laird Hamilton’s house, doing Laird’s infamous pool workout with a bunch of superstars that includes retired Indiana Pacers All-Star Reggie Miller, world champion Thai boxer Tom Jones, and, curiously, legendary music producer Rick Rubin. For two hours straight Olien engages in grueling exercises with names like ammo box and seahorse that mostly involve running and lunging with weights, 10 feet underwater. The idea is to build strength, stamina, and lung capacity for big wave wipeouts and epic calm in the face of terror. Halfway through, Miller says, “This is the hardest athletic thing I’ve ever done. I’d rather set a pick on Shaq.” The only athlete who keeps up with Hamilton is Olien, who pointedly consumes Shakeology—and only Shakeology—before and after the pool session.

Heller is a Bloomberg Businessweek contributor.